|

Texas has banished hundreds of prisoners to more than a decade of solitary confinement, an extreme form of a controversial punishment likened to torture. Many of these prisoners aren’t sure how—or, in some cases, if—they will ever get out.

Read more...

0 Comments

SPOTLIGHT: SUPPORTING SOLITARY FOR MANAFORT MEANS SUPPORTING IT FOR EVERYONE

The Appeal: Vaidya Gullapalli June 05, 2019 Yesterday the news broke that Paul Manafort, President Trump’s former campaign head who was sentenced to seven and a half years in prison on federal charges, will now face criminal charges in state court in Manhattan. The New York Times reports that Manafort will most likely be held at Rikers Island, segregated from the general population. Though it is not clear that Manafort would be confined to his cell even if he is isolated, many reports have said he will be in “solitary confinement.” Tens of thousands of people, by conservative estimates, spend their days in solitary confinement cells in jails and prisons across the United States. (An oft-cited estimate of 61,000 people in isolation nationwide is understood, including by those who arrived at it, to be a substantial undercount.) But it made news that Manafort was expected to be sent to Rikers and isolated. Some responded with satisfaction to the report that a previously powerful rich white man, closely associated with the president, would be subjected to the same abuse as masses of poor Black and brown people. But that response is an example of how ending injustice can seem so impossible that our hopes warp into a desire to expand injustice. The problem is not that the Manaforts of the world don’t usually spend time in solitary, or in prison. The problem is that tens of thousands of people around the country sit in what are, effectively, torture chambers. Read More Solitary confinement worsens mental illness. A Texas prison program meant to help can feel just as isolating.

The Texas Tribune BY JOLIE MCCULLOUGH APRIL 23, 2019 Prisoners who volunteered for a mental health diversion program say promises of therapy and time out of their cells weren't fulfilled. And Texas prison officials aren't regularly tracking success rates — even as they ask lawmakers to fund an expansion of the program. Read More My jail stopped using solitary confinement. Here's why.

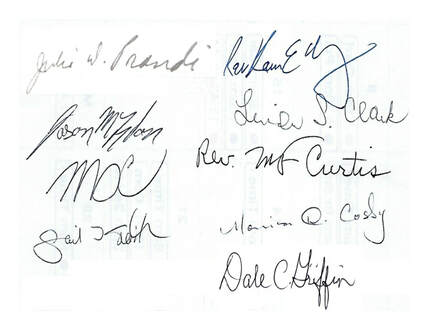

The Washington Post by Tom Dart April 4, 2019 Tom Dart is sheriff of Cook County, Ill. Recent criminal-justice reform ended the use of solitary confinement for juveniles in federal prisons. Now a group of lawmakers including Sen. Richard J. Durbin (D-Ill.) and presidential candidate Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) are pushing to limit solitary confinement in federal prisons more broadly. However, the realities of solitary confinement playing out in other correctional institutions across the country — including county jails, like the one I run — remain unaddressed and misunderstood. Whether termed solitary confinement, disciplinary segregation or something else, it is almost always the same thing and produces the same disturbing and, too often, grave consequences. Individuals are confined alone in roughly 7-by-11-foot concrete cells for up to 23 hours a day with little human contact and no access to natural light. For as few as 60 minutes a day, they are allowed out of their cells to pace about another concrete area no larger than a dog run. In some cases, it’s outdoors; in others, not. This punishment is meted out for reasons ranging from disobeying an officer’s order to violent assaults on staff, and it can last anywhere from 24 hours to years. Most facilities make no accommodation for detainees suffering from severe mental illness. And the damage solitary inflicts on people is indisputable. Years of research have demonstrated that the effects include mental illness, anger, despondency and self-harm; psychiatrist Stuart Grassian concluded that solitary can cause a specific psychiatric syndrome that includes hallucinations, panic attacks and paranoia. Of course, some kind of disciplinary mechanism is needed, because jails are inherently volatile. Unlike prisons, jails generally don’t house people who have been convicted and sentenced — the population is overwhelmingly made up of people awaiting trial. At my jail in Cook County, Ill. — one of the nation’s largest, with about 5,500 detainees — we have seen an increasing length of stay for individuals in our custody, for many reasons including a painfully slow-moving criminal-justice system. Several of our current detainees have been here nearly 10 years without adjudication. Add to that frustration, the presence of members of fractious Chicago street gangs and society’s de facto decision to jail the mentally ill, and it’s easy to see how jails can become violent places. However, the solution to that violence is not solitary confinement. I know there is a better way. I know because we have been doing it differently here in Chicago for nearly three years now. After years of handling violence just like most other jails, we realized that solitary was not solving the problem. It was contributing to it. And so, since May 2016, we have not housed any detainee in a solitary setting, not for even one hour. Instead, we created a new place in the jail called the Special Management Unit (SMU) to house detainees who resort to violence and/or break the rules. There they can spend time in open rooms or yards with other detainees — as many as six or eight at a time — under direct supervision by staff members trained in conflict deescalation and resolution techniques and with precautions in place to ensure safety. Mental-health professionals provide weekly sessions on anger management, coping skills and conflict resolution. We also changed the disciplinary process for infractions to include other programming including thoughtful hearings and increased classes and activities . Staffers, though skeptical at first, have been amazing. They have bought into this alternative to using isolation as a cudgel. After all, these new practices have not just benefited our detainees, they have also improved our working conditions. Since we introduced this model to our jail, detainee-on-detainee assaults have dropped significantly and assaults on staff plummeted. Last year we recorded the lowest number of total assaults since the SMU was established. While the national discussion on criminal-justice reform tends to focus on sentencing, we must also reexamine the conditions of confinement we employ in jails, particularly the use of solitary. No reputable study has ever documented any positive effects from solitary confinement. Regardless of your position on criminal-justice reform, you should realize that more than 70 percent of our jail detainees do not spend the rest of their days in prison — rather, they are released and return to their communities. This may be because charges against them are dropped, bonds are paid, plea agreements are signed, or they go to trial and are found not guilty. In all those cases, the result is the same — they are released from jail. What are we doing to our communities when we send them people, suddenly unmonitored, who have spent the past few months of their lives in a concrete room, devoid of any human contact? The results often involve violence, volatility and recidivism. It is time solitary is addressed and eliminated in jails around the country. Dear Governor Pritzker, We applaud the interest you have shown in reforming the Illinois prison system. You have said that you place much of your focus on “not just avoiding recidivism and reducing the prison population by perhaps having different sentences, but also keeping people out of prison in the first place.” We implore you to remember that these are deeply related; the welfare of people currently incarcerated impacts their loved ones who remain at home both in their absence and their eventual return to their communities. How people are treated while in prison has human repercussions that powerfully impact recidivism rates and also the opportunities of those close to them, most importantly, their children. As you move to appoint the next Director of Corrections, we urge you to consider candidates who are skeptical about current uses of segregation (also called solitary confinement) for adult prisoners. It is inspiring to realize that heads of correction in three states have spearheaded and effectively implemented strict limits on segregation. Significantly, such efforts have indeed often been led by prison officials themselves, giving the lie to those who maintain that curbing solitary endangers prison staff or removes a necessary disciplinary option. A limit of 15 consecutive days on segregation has been adopted by legislators in New Jersey and Canada; that would be a laudable goal for Illinois. Signed – Members of the Unitarian Universalist Prison Ministry of IL : Steering Committee CC: Lieutenant Governor Stratton

The following is supplemental and anecdotal evidence of the success other states have achieved in this matter: In 2015, the Association of State Correctional Administrators, the leading organization for the nation’s prison and jail administrators, called for sharply limiting or even ending solitary confinement for extended periods. Since the ASCA was largely responsible for past increases in the use of solitary confinement, this represents a significant change of course. Colorado, Mississippi, and Maine serve as successful examples where changes launched by the executive branch of state government, with the help of progressive Directors of Corrections. Colorado, under the supervision of their director of corrections Rick Raemisch, has led the way nationally in implementing the most aggressive limits on solitary confinement. Raemisch’s agency has limited the use of solitary confinement in Colorado to 15 days at a time. As Raemisch writes, “The problem is that [solitary confinement] was not corrective at all. It was indiscriminate punishment that too often amounted to torture and did not make anyone safer.” Mississippi Corrections Commissioner Christopher Epps, testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2012, noted what his department had accomplished: “The Mississippi Department of Corrections administrative segregation reforms resulted in a 75.6% reduction in the administrative segregation population from over 1,300 in 2007 to 316 by June 2012.” Commissioner Joseph Ponte of Maine was inspired by Mississippi’s solitary reform efforts. Once he heard the story of Epps’s success, he felt, “if he can do that in Mississippi I know we can do that in Maine.” The Department of Corrections in Maine overhauled its use of long-term isolation without being ordered to by a judge or a piece of legislation. Maine, too, can serve as an example for what is possible in solitary confinement reform. As you know, the 2015 settlement of the federal lawsuit concerning the use of segregation in Illinois juvenile prisons requires that the juvenile prisoners spend at least eight hours per day outside their cells and that young people in isolation continue to receive education and mental health services. Adults in prison, many of whom are young themselves, deserve the same opportunities for growth and healing. When changes in segregation policy can be enacted by Directors of Corrections, as has been accomplished in Colorado, Maine and Mississippi, Illinois should not have to wait for another lawsuit to do what is right, and what is most effective for rehabilitation purposes—by limiting the use of solitary confinement. This session there is a bill, HB 182, that would limit solitary confinement to not more than 10 days in any 180 day period while also guaranteeing prisoners in solitary access to classes, recreation, visits and group therapy. Whether or not this bill becomes law, the support of the new head of IDOC and of you, Governor Pritzker, is crucial to getting Corrections staff trained and on board for significant prison reform and for success in implementing any changes in corrections policies. International law also recognizes the importance of limiting solitary confinement. In 2014, the United Nations Committee Against Torture (CAT) released a report reviewing U.S. compliance with the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. That report cites the excessive use of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons and jails as a violation of the Convention Against Torture and suggests major reforms. Meanwhile, in New Jersey and in Canada, officials have decided to abide by the UN Standard Minimum Rules for Treatment of Prisoners (also known as the “Nelson Mandela Rules”). These rules prohibit solitary confinement (defined as isolation of a prisoner for more than 22 hours per day without meaningful human contact) that is longer than 15 consecutive days (Rule 43 and 44). In 2016, New Jersey lawmakers voted to stop isolating prisoners for as long as 23 hours a day for months or years on end after deciding it was abusive and it hampered their return to society. Now, use of solitary confinement is a last resort in New Jersey, limited to no more than 15 days at a time. In addition, a physician, clinical psychologist or psychiatric nurse monitors anyone subject to solitary confinement. In 2017 the Canadian federal government decided to phase in a cap of 15 days of solitary confinement. As the Vera Institute of Justice noted in its 2018 annual report: “Every day, approximately 60,000 people are held in solitary confinement in America’s prisons, and since the 1980s, our prisons and jails have increasingly relied on this cruel practice to maintain order. But solitary can damage, sometimes irreparably, people who experience it for even brief periods of time, and it stops incarcerated people from developing the skills they need to successfully return to their communities.” On a practical level, segregation is also expensive to administer. Solitary confinement has been shown to exacerbate mental illness and incite inmates to repeated self-harm, including suicide attempts. It should not greatly surprise anyone that when people are isolated in small cells for 23 hours per day, they begin to behave like animals. “If you treat people like animals, that’s exactly the way they’ll behave,” said Mississippi DOC Commissioner Epps, in his testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee. He added that transitioning prisoners in Mississippi’s Unit 32 out of solitary confinement “...worked out just fine. We didn’t have a single incident.” As the ACLU noted, “solitary confinement jeopardizes our public safety, is fundamentally inhumane and wastes taxpayer dollars. We must insist on humane and more cost-effective methods of punishment and prison management.” In sum, changing how solitary confinement is used is imperative for the mental and physical health of prisoners, for the well- being of their families and the communities they will re-enter, and for the safety of all prisoners and correctional staff. Whatever the eventual fate may be of HB 182, we urge you to be inspired by states from Colorado to Maine and to appoint a Director of Corrections for our state who has demonstrated a commitment to prison reform, specifically enforcing a maximum of 15 days in solitary confinement per year, or, as Representative Ford's legislation mandates, a maximum of 10 days in solitary confinement per 180 days." ***** References ****** Brian Mackey, Here and Now, “J.B. Pritzker Interview – On Criminal Justice, Higher Ed, Taxes, And Legislative Ethics,” npr Illinois, Jan 13, 2019, Feb 20, 2019, http://www.nprillinois.org/post/jb-pritzker-interview-criminal-justice-higher-ed-taxes-and-legislative-ethics#stream/0 Timothy Williams, The New York Times, “Prison Officials Join Movement to Curb Solitary Confinement,” Sept, 2, 2018, Feb 20, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/03/us/prison-directors-group-calls-for-limiting-solitary-confinement.html Rick Raemisch, Speak Freely, “Why I Ended the Horror of Long-Term Solitary in Colorado’s Prisons,” ACLU, December 5, 2018, Feb 20, 2019, https://www.aclu.org/blog/prisoners-rights/solitary-confinement/why-i-ended-horror-long-term-solitary-colorados-prisons Vera Annual Report, “Embracing Human Dignity,” Vera Institute of Justice, 2018, Feb 20, 2019, https://storage.googleapis.com/vera-web-assets/downloads/Publications/annual-report-2018-embracing-human-dignity/legacy_downloads/embracing-human-dignity-annual-report-2018-2.pdf Alex Friedmann, Prison Legal News, “Solitary Confinement Subject of Unprecedented Congressional Hearing,” Prison Legal News, Oct 15, 2015, Feb 20, 2019, https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2012/oct/15/solitary-confinement-subject-of-unprecedented-congressional-hearing/ ACLU, “We Can Stop Solitary,” ACLU, Feb 20, 2019, https://www.aclu.org/issues/prisoners-rights/solitary-confinement/we-can-stop-solitary Virginia prison officials say they eliminated solitary confinement. Inmates say they just gave it a new name. 'It's all very Hannibal Lecter-ish'

Virginia Mercury by Ned Oliver January 14, 2019 Virginia prison officials say they’re on the leading edge of corrections reform for “operating without the use of solitary confinement.” But Derek Cornelison, a 34-year-old inmate at Red Onion, one of the state’s two supermax prisons in Wise County, says he and dozens of other prisoners have remained isolated in tiny cells for 22 to 24 hours a day for years — a level of confinement increasingly viewed as cruel, inhumane and a violation of international human rights standards. Read More The Love Story that Upended the Texas Prison System

Texas Monthly by Ethan Watters October 11, 2018 In 1967, a 56-year-old lawyer met a young inmate with a brilliant mind and horrifying stories about life inside. Their complicated alliance—and even more complicated romance—would shed light on a nationwide scandal, disrupt a system of abuse and virtual slavery across the state, and change incarceration in Texas forever. On November 9, 1967, Fred Cruz was in his sixth year of a fifteen-year robbery sentence and starting yet another stint in the hole. Of the many punishments the Texas prison system doled out to inmates, solitary confinement was one of the most brutal on the body and the soul. It wasn’t Cruz’s first time there, but it wasn’t something one got used to. The Ellis Unit, about fourteen miles north of Huntsville in a boggy lowland area of East Texas, was known as the toughest prison in the system, and there was no worse place to be in Ellis than solitary. The cell’s darkness was so complete it made the eyes ache. On some occasions, Cruz was given a thin blanket and nothing else—no clothes and no mattress for the steel bunk. His toilet was a hole in the floor. He’d receive only three slices of bread a day with a full meal twice a week, and had shed multiple pounds from his already thin frame. After two weeks, an outer door to the cell would be opened, allowing in light from the hallway. This would be considered a “release” from solitary. Then the warden or an officer would come by and assess the sincerity of Cruz’s contrition. If he failed that yes-sir-no-sir encounter, the solid steel door would be shut again and the days of darkness would recommence. Read More Investigation into inmate’s suicide faults Maryland women’s prison’s treatment of people with disabilities

Washington Post By Lillian Reed December 15 An investigation into Maryland’s only prison for women following the 2017 suicide of an inmate found the facility violated the constitutional rights of people with disabilities who are placed in segregation and did not take sufficient steps to “prevent future harm.” The investigation, released Friday by Disability Rights Maryland, reviewed the Maryland Correctional Institution for Women and its role in the death of inmate Emily Butler, who was found dead in her cell from an apparent suicide on Nov. 12, 2017. The investigative report details several findings and recommends changes on how the prison can better handle inmates with disabilities. Disability Rights Maryland is the state’s designated authority under federal law for conducting investigations into allegations of abuse and negligence for people with disabilities. The group, along with Munib Lohrasbi of the Open Society Institute of Baltimore, launched a review after Butler’s death in segregation. Read More North Dakota Prison Officials Think Outside The Box To Revamp Solitary Confinement

NPR :: July 31, 2018 :: Cheryl Corley Thousands of inmates serve some of their time in solitary confinement, locked down in small cells for up to 23 hours a day. North Dakota is changing its thinking on this segregated housing. There are slightly more than 2 million people incarcerated in the United States — that's nearly equal to the entire population of Houston. Among those prisoners, thousands serve time in solitary confinement, isolated in small often windowless cells for 22 to 24 hours a day. Some remain isolated for weeks, months or even years. ... Read the full story When They Get Out: how prisons

Atlantic (1999) by Sasha Abramsky Popular perceptions about crime have blurred the boundaries between fact and politically expedient myth. The myth is that the United States is besieged, on a scale never before encountered, by a pathologically criminal underclass. The fact is that we're not. After spiraling upward during the drug wars, murder rates began falling in the mid-1990s; they are lower today than they were more than twenty years ago. In some cities the murder rate in the late twentieth century is actually lower than it was in the nineteenth century. Nonviolent property-crime rates are in general lower in the United States today than in Great Britain, and are comparable to those in many European countries. Read More |

What this is aboutLearning asks us to change – so that the world might be a place for all are free to thrive Categories

All

Archives

February 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed