|

I Got to Leave Prison for a Few Hours - It Broke My Heart

Marshall Project By Byron Case The guards wake me by slamming the lock on my cell's sliding door, a noise like an aluminum stepladder abruptly collapsing. My alarm clock reads 4:17 a.m. Disoriented with sleep, I wonder if I'm still dreaming. The truth dawns incrementally: My long-awaited hospital visit must be today. I reach for the gray pants and white T-shirt folded on my foot locker. This movement's too sudden. My heart starts pounding, and I'm instantly nauseated, but this is nothing new. In fact, it's the reason I've been awakened at this unthinkable hour in the first place. There are only so many health issues that the prison is equipped to deal with. On-site medicos did refer me to a cardiologist in what prisoners often give the fantastical appellation “the outside world.” Unfortunately, the bureaucracy's taken three and a half long, anxiety-riddled months to okay me to see one. Learning I'd been approved gave me a measure of relief, but I had no clue just when I'd be going out. To minimize the chance of escape attempts, the powers that be treat as top secret the date and time of trips beyond the facility's boundaries. Read More

0 Comments

Prisoners Unlearn The Toxic Masculinity That Led To Their Incarceration

Huffington Post by Anna Lucente Sterling July 31, 2019 In prisons across California, inmates are unlearning toxic masculinity. It might be the answer to the state’s recidivism problem. It’s been 10 years since George Luna was behind bars, but he still goes back to correctional facilities on a regular basis. He has spent most of his life cycling in and out of the justice system in Northern California. Now, he says he’s out for good and he’s looking to help other inmates do the same. The former inmate is a facilitator of a prison rehabilitation program that teaches men about gender roles and how ingrained ideas of masculinity have contributed to their violent crimes. GRIP, or Guiding Rage into Power, started at San Quentin State Prison in 2013 and has expanded to five state prisons across California. Read, Watch and Listen More A CHICAGO JAIL MIGHT BE THE LARGEST MENTAL HEALTH CARE PROVIDER IN THE U.S.

Pacific Standard by Arvind Dilawar June 10, 2019 After Illinois cut funding for mental-health services, Cook County Jail now handles a large portion of the state's patients. A new book tells their story. "Mental ward / is where I landed," begins a poem by Marshun, an inmate at Cook County Jail in Chicago. The poem describes Marshun's struggle with bipolar disorder, as well as his appreciation for flowers and photography. He was diagnosed before first entering Cook County Jail, where he's been an inmate on and off since he was 20 years old, but it was only during his most recent stint at 33 that he entered the Mental Health Transition Center, a program that provides inmates with mental-health services. "If I had come to this program when I was 20," Marshun says, "I wouldn't have come back to jail." Marshun's story is just one of many that photographer Lili Kobielski captures in her recent book, I Refuse for the Devil to Take My Soul, a revealing collection of portraits and interviews from inside Cook County Jail. The facility is not only one of the largest jails in the United States, but it may also be the nation's largest mental health care provider. Many inmates receive mental-health treatment at Cook County Jail simply because it is the provider of last resort. Beginning in 2009, the state government of Illinois crippled its health-care system, slashing nearly $114 million in funding from mental-health services and depriving 80,000 residents of access to mental-health care through budget impasses. As a result, two state-operated facilities and six city clinics closed, two-thirds of non-profit agencies in Illinois reduced or eliminated programs, and a third of Chicago's mental-health organizations lowered the number of patients they served. Read More When Abuse Victims Commit Crimes

The Atlantic by Victoria Law May 21, 2019 On a morning this past March, two dozen women gathered on a Harlem sidewalk. Many had been released from prison over the past decade. They were boarding a charter bus to Albany, where they hoped to persuade state senators to vote for a new bill that could keep women like them—victims of domestic violence—from getting sent to prison. The bill in question, the Domestic Violence Survivors Justice Act, which was signed into law this past week, gives judges more options when sentencing individuals who have been convicted of violence against abusive partners or other crimes that such partners had coerced them into committing. Instead of being required to hand out predetermined sentences for particular crimes, judges could instead mete out shorter prison terms or avoid incarceration altogether. Several of the women on the bus that day spent years in prison for acts involving abusive partners. One told me that she spent more than 17 years behind bars for fatally shooting her boyfriend in the neck while he was choking her. Another told me that when her partner wrapped his hands around her neck and began choking her, she grabbed for the nearest object—a knife—and thrust it. The man died, and she was charged with murder and sentenced to 19 years to life. (The names of these women are being withheld for their privacy. They requested that The Atlantic refrain from contacting their former partners or their families, for fear of retaliation. Their crimes are corroborated by police records.) Read More Behind Bars for 66 Years

The Marshall Project by Joseph Neff May 23, 2019 ASHEBORO, N.C. — John Phillips has been behind bars since April 8, 1952, when he was arrested on sexual-assault charges. He was 18 years old and only in the ninth grade, and he was sent to be evaluated at the state mental hospital for black people. The report classified Phillips as a “moron” and said he had the mind of a child aged 7 years and 7 months. His lawyer entered a guilty plea. The judge sentenced him to life. After 66 years in prison, Phillips is the state’s longest-serving inmate, a stooped and garrulous 85-year-old man whom inmates nicknamed Peanut and who gets around with the help of a worn wooden cane. Decades ago he lost his desire to live outside of razor-wire fences. Read More My jail stopped using solitary confinement. Here's why.

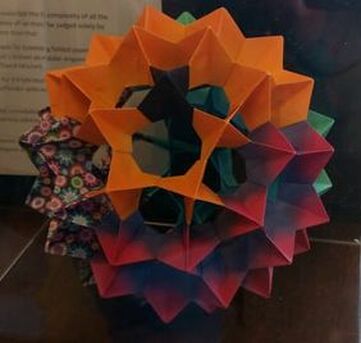

The Washington Post by Tom Dart April 4, 2019 Tom Dart is sheriff of Cook County, Ill. Recent criminal-justice reform ended the use of solitary confinement for juveniles in federal prisons. Now a group of lawmakers including Sen. Richard J. Durbin (D-Ill.) and presidential candidate Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) are pushing to limit solitary confinement in federal prisons more broadly. However, the realities of solitary confinement playing out in other correctional institutions across the country — including county jails, like the one I run — remain unaddressed and misunderstood. Whether termed solitary confinement, disciplinary segregation or something else, it is almost always the same thing and produces the same disturbing and, too often, grave consequences. Individuals are confined alone in roughly 7-by-11-foot concrete cells for up to 23 hours a day with little human contact and no access to natural light. For as few as 60 minutes a day, they are allowed out of their cells to pace about another concrete area no larger than a dog run. In some cases, it’s outdoors; in others, not. This punishment is meted out for reasons ranging from disobeying an officer’s order to violent assaults on staff, and it can last anywhere from 24 hours to years. Most facilities make no accommodation for detainees suffering from severe mental illness. And the damage solitary inflicts on people is indisputable. Years of research have demonstrated that the effects include mental illness, anger, despondency and self-harm; psychiatrist Stuart Grassian concluded that solitary can cause a specific psychiatric syndrome that includes hallucinations, panic attacks and paranoia. Of course, some kind of disciplinary mechanism is needed, because jails are inherently volatile. Unlike prisons, jails generally don’t house people who have been convicted and sentenced — the population is overwhelmingly made up of people awaiting trial. At my jail in Cook County, Ill. — one of the nation’s largest, with about 5,500 detainees — we have seen an increasing length of stay for individuals in our custody, for many reasons including a painfully slow-moving criminal-justice system. Several of our current detainees have been here nearly 10 years without adjudication. Add to that frustration, the presence of members of fractious Chicago street gangs and society’s de facto decision to jail the mentally ill, and it’s easy to see how jails can become violent places. However, the solution to that violence is not solitary confinement. I know there is a better way. I know because we have been doing it differently here in Chicago for nearly three years now. After years of handling violence just like most other jails, we realized that solitary was not solving the problem. It was contributing to it. And so, since May 2016, we have not housed any detainee in a solitary setting, not for even one hour. Instead, we created a new place in the jail called the Special Management Unit (SMU) to house detainees who resort to violence and/or break the rules. There they can spend time in open rooms or yards with other detainees — as many as six or eight at a time — under direct supervision by staff members trained in conflict deescalation and resolution techniques and with precautions in place to ensure safety. Mental-health professionals provide weekly sessions on anger management, coping skills and conflict resolution. We also changed the disciplinary process for infractions to include other programming including thoughtful hearings and increased classes and activities . Staffers, though skeptical at first, have been amazing. They have bought into this alternative to using isolation as a cudgel. After all, these new practices have not just benefited our detainees, they have also improved our working conditions. Since we introduced this model to our jail, detainee-on-detainee assaults have dropped significantly and assaults on staff plummeted. Last year we recorded the lowest number of total assaults since the SMU was established. While the national discussion on criminal-justice reform tends to focus on sentencing, we must also reexamine the conditions of confinement we employ in jails, particularly the use of solitary. No reputable study has ever documented any positive effects from solitary confinement. Regardless of your position on criminal-justice reform, you should realize that more than 70 percent of our jail detainees do not spend the rest of their days in prison — rather, they are released and return to their communities. This may be because charges against them are dropped, bonds are paid, plea agreements are signed, or they go to trial and are found not guilty. In all those cases, the result is the same — they are released from jail. What are we doing to our communities when we send them people, suddenly unmonitored, who have spent the past few months of their lives in a concrete room, devoid of any human contact? The results often involve violence, volatility and recidivism. It is time solitary is addressed and eliminated in jails around the country.  Marilyn Many people view inmates from a very limited perspective, looking at only a single point in their lives. My origami sculpture represents that I am more than a singular point in time. I am so much more that just that one piece. It is a representation of how each piece of my life is intricately woven and interconnected to the others, all interdependent on each other, forming a complex, multidimensional whole. This sculpture is composed on 60 pieces of folded paper. The composition of this sculpture has symmetry. As a representation of myself, each piece of paper is interconnected to form a dynamic whole that gets its strength using nothing more than its individual pieces to hold it together. Each piece has its own power, each slightly different from the other, but all necessary for the balance and equilibrium of the whole. The paper colors were chosen to represent the different aspects of my life some very bright and flowery, some contrasting, others complementary. The black piece represents the tragic circumstances that brought me to prison. It is my hope that this sculpture will help to remind others to acknowledge the full complexity of all the pieces that shape our lives. EVERYONE has a complex life story. None of us should be judged solely by the piece that is the worst thing we’ve done. We are so much more than that. A little about this origami technique: my paper sculpture was made by assembling folded paper modules into an integrated, 3-dimensional form, a technique that’s known as modular origami. This sculpture is based on a paper crystal design created in 1989 by David Mitchell. Biography: I am a 61 year-old woman, incarcerated since 1999 for a triple murder. I’m serving a natural life sentence without the possibility of parole. I’m a first-time offender with no criminal history in my background. As I tried to represent with my artwork, I’ve had a complex and convoluted journey leading to my incarceration. I was diagnosed with major depression and a serious adverse side effect of the prescribed antidepressant played a major role in my crime. I started doing origami in prison as a creative outlet. I’ve become an origami enthusiast and have shared the joy of origami with other inmates by facilitating many origami activities. Prison inmate describes conditions during 23-Day lockdown.

Channel 3000 News by Jamie Perez February 7, 2019 "Although they told you guys we were getting hot meals, it took at least a week before we got a hot meal," Dontrell LeFlore said. "That was only Monday through Friday. We were asking them, 'What's up with the weekend?' And they were like, 'Well, no hot meals on the weekend.' It was hard to get this information out because we couldn't call home. We were scared to write because they open up our mail before it goes out. Now speaking out, I'm putting myself at risk. Being cut off from the world like that, that has never happened. In my 19 years in prison, I have never spent that much time without access to a phone or a visit." Read More Life Inside: I'm in Prison During the Shutdown

The Marshall Project by Seth Piccolo January 17, 2019 We wait by the door for our turn at chow. It's Christmas dinner—really, early lunch since it's only 10:30 in the morning. Here, holiday meals are something to look forward to. They're never great, but the guys in the kitchen try hard. The government is shut down right now so we're lucky to be having a holiday meal at all. Some of the officers here are getting a little touchy. Yesterday I saw an inmate ask one if she was going to open the music room. She stood there for a beat looking off somewhere else, then responded, "What I'm not going to do is be pushed during this shut down!" It gets a little more complicated being an inmate during these times, but finding yourself in a position in life where you have little to no power teaches you patience. We just shake our heads and laugh it off. The phones haven't been working for the last few days. No calls are going out. It's a bad time for this to happen, it being the holidays. Everyone wants to call home, especially on Christmas. Read More Investigation into inmate’s suicide faults Maryland women’s prison’s treatment of people with disabilities

Washington Post By Lillian Reed December 15 An investigation into Maryland’s only prison for women following the 2017 suicide of an inmate found the facility violated the constitutional rights of people with disabilities who are placed in segregation and did not take sufficient steps to “prevent future harm.” The investigation, released Friday by Disability Rights Maryland, reviewed the Maryland Correctional Institution for Women and its role in the death of inmate Emily Butler, who was found dead in her cell from an apparent suicide on Nov. 12, 2017. The investigative report details several findings and recommends changes on how the prison can better handle inmates with disabilities. Disability Rights Maryland is the state’s designated authority under federal law for conducting investigations into allegations of abuse and negligence for people with disabilities. The group, along with Munib Lohrasbi of the Open Society Institute of Baltimore, launched a review after Butler’s death in segregation. Read More |

What this is aboutLearning asks us to change – so that the world might be a place for all are free to thrive Categories

All

Archives

February 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed